The power that media users possess in regards to the types of media they choose to consume is overwhelming. This power can be most evident when discussed in the realm of viewership and television ratings. If a show does not develop a strong fan base that watches every week, that television show will be canceled by the network. On the other hand, if a television show develops a strong fan base, the network will negotiate a contract to get more seasons from the show. Now, think about this in terms of film. Certain films will garner a strong critical reception or profitable box office numbers. Other films can develop a strong fan base in which fans engage in ritualistic like activities for the film. The definition of a cult film is so elusive because any film can become a cult film.

The 70s and 80s brought in a new wave of cinema that revolutionized not only how many viewed cinema at the time but also how one would experience a film within the cinematic experience. VHS was not introduced to Americans until the late 70’s and as a result, an enormous amount of importance was placed upon the theater experience. In the current climate of technology, a media user possesses the ability to view films through a manner of on-demand programs and streaming services and thus the theater experience is no longer a priority as it was in the 70s. With the focus placed on theaters, cinephiles found a place in which they could have a social experience with others over cherished motion pictures.

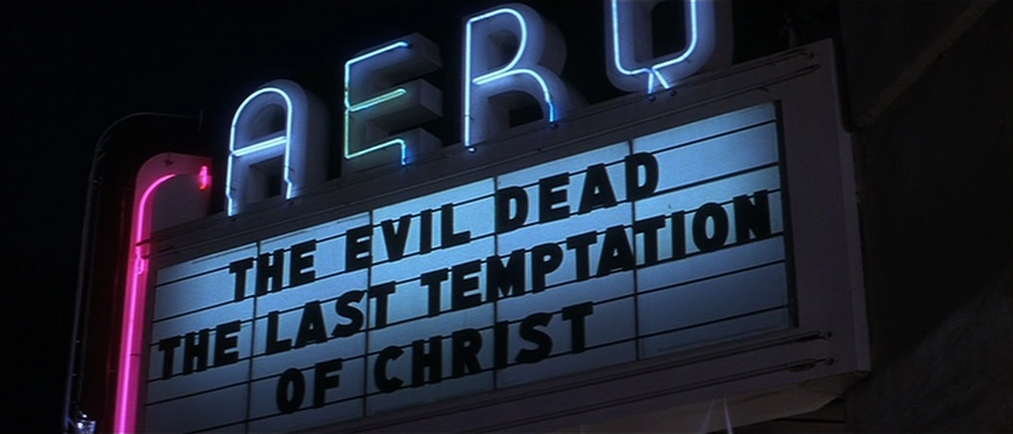

This sense of community helped films develop an audience. According to Tim Dirks, “the first ‘official’ midnight movie showcase was of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film El Topo (1970).”[1] Throughout the 70’s, midnight movie screenings would begin to take place in certain parts of the country. Gregory A. Waller studied the midnight bookings of the Kentucky Theatre in Lexington, Kentucky. Waller discovered these midnight screenings showcased a wide variety of films. From films such as The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), to Animal House (1978), to The Warriors (1979).[2] The diversity amongst these films is important but so is the fact that these midnight movie screenings were happening weekly and these showcases brought together cinephiles in a social manner.

While midnight movie showcases exist today, some believe they do not bring together cinephiles as they once did. In the Cineaste magazine article, “Cult Film: A Critical Symposium,” David Church interviews multiple scholars in regards to cult films. I.Q. Hunter, a professor from De Montfort University, had quite the answer when asked about the social role of cult films: “I’m not sure cult films have a social function. They may have done so in the 1970’s when screenings showcased the preferences of the counter culture and sexual underground.”[3] Hunter brings forth an interesting point upon mentioning a counter culture. Great focus should be placed upon this counter culture when discussing cult films.

The concept of a cult film has existed within the film community for decades, while there has been some work done in this field of academic discussion, no definitive definition has been pressed upon cult films. Instead, different scholars have different views in regards to what it takes for a film to be a cult film. Some cult films are beloved for being a bad film, others become so because they rebel against the status quo. One key consistency exists, however, within the context of the fans that surround cult films and the activities they engage in while viewing these cult films: no filmmaker has set out with the intentions of creating a cult film. Instead, the viewers possess the ability to elevate these films to another level. In the aforementioned Cineaste article David Church writes, “A cult film has a select but eccentrically devoted audience who engage in repeated screenings, celebratory rituals, and/or iconic reading strategies.”[4] The most important pillar holding up the cult film phenomena is the fan base that utilizes its agency to give this film the cult film status.

Certain cult films develop a strong audience by rejecting the mainstream norm. Some films that encapsulate this resistance are A Clockwork Orange (1971), Easy Rider (1972), and The Warriors (1979). Two years after the release of A Clockwork Orange in the United Kingdom, director Stanley Kubrick made the tough decision to pull the film from theaters. Due to claims of “copycat violence” and accusations that the film would influence viewers to do harm unto others, Kubrick decided to no longer distribute the film to theaters in the United Kingdom.[5] The controversy surrounding this decision snow balled into the previously-existing controversy that engulfed many of the book’s readers. This controversy pushed forward the narrative that A Clockwork Orange was not fit for mainstream consumption and those who sought out opposition to mainstream consumerism found delight when viewing the film.

Another cult classic film found itself a beneficiary of controversy, the dystopian crime film The Warriors.[6] Danny Peary discusses the original advertisement of the film which caused a stir with its assertion that gangs could consume New York.[7] The advertisement startled many citizens of New York and forced fans of the film into defense. Peary writers, “As the cultists charged, it was the ad, not the film, which drew excitable undesirable elements to the theater.”[8] The controversy helped push against a mainstream thought process again and helped propel The Warriors into a special position amongst fans.

A true testament to this counter culture thought process is the 1969, Dennis Hopper directed film Easy Rider.[9] Easy Rider was produced on a small budget unlike other Hollywood, mainstream consumerism driven films. Easy Rider was produced with an estimated budget of $400,000 but the film garnered $60,000,000.[10] Mark Shiel writes about Easy Rider and its director: “Dennis Hopper, in particular, saw himself as an antagonist outsider assaulting Hollywood.”[11] Dennis Hopper himself feels as though he is a part of this counter cultural rejection of mainstream consumerism, specifically Hollywood.

A much more contemporary film that can fit snug into this counter culture push in the film industry is the Kevin Smith directed 1994 film Clerks.[12] Much like Easy Rider, Clerks was shot and produced for an estimated $260,000.[13] This film focused on the Generation X working class population as it presented a neo-realistic style of storytelling. Much of the humor is considered crude and inappropriate, helping this film push away the mainstream sense of comedy and helped to usher in much of the crude comedy we see today.

Another type of cult film is that of the nostalgic cult film. One example of this type of cult film is one that had a tremendous impact on the millennial generation is the 1996 film Space Jam.[14] This film features one of the most iconic basketball players of all time, specifically iconic within the 90s, Michael Jordan. It features Looney Tunes characters that elicit a strong reaction due to their historical presence. Many from my generation consider this to be a nostalgic film that sparks many fond memories. In the book Cult Cinema, Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton write about Grease (1978)[15] as a nostalgic cult film: “Therefore, a film that was originally nostalgic about an imagined past has now itself become an object of nostalgia…”.[16] Another example of a nostalgic cult film is the 1985 film The Breakfast Club.[17] While many who love this film were most likely adolescents during its initial theatrical run, the film has transcended that audience and people of a younger generation watch this film as if it is a time capsule of the 80s.

Danny Peary explains one trait of a cult film is as follows, “‘definitive’ performances by stars who have cult status.”[18] An excellent example of Peary’s aforementioned trait is the film Rebel Without A Cause (1955), a film which featured the actor James Dean. While James Dean only starred in three films in his lifetime, he is viewed as a cultural icon. James is described as “Epitomizing the outsider with a poetic sensibility, his characters sought to establish their identity apart from peer pressure and materialistic adult values”.[19] Jim Stark, the character Dean portrays in Rebel Without A Cause, is one of the most iconic film characters of all time and created a reoccurring archetype within every teen coming of age film to date.

A category of cult films that many cultists enjoy is that of the “so bad it is good” category.[20] To conclude a film could be so bad it is worthy of examination, requires one to understand the distinction of a good film and a bad film. The ability to enjoy and appreciate a film of poor quality means one must know how to examine what many consider a “good” movie. This argument can become subjective as there is no cult status for a film like The Superhero Movies (2008), yet, The Room is not only the film to exist within this realm of cult film status. When discussing these types of films, the film that is most frequently interjected into this category is the film The Room (2003). Ross Morin writes “It exposes the fabricated nature of Hollywood. The Room is the Citizen Kane of bad movies.”[21]

Ed Wood directed a film in 1956 titled Plan 9 From Outer Space, another movie “so bad it is good”. Barry K. Grant writes: “Similarly, his [Ed Wood] 1956 effort Plan 9 From Outer Space is a cult narrative favorite because it is so obviously awful in the context of the well-made classical narrative.”[22] The viewer truly possesses the ability to take what should be considered a bad film and appreciate it in the same way they would a movie of high quality.

Other films have received a special type of treatment by cultist fans. These films were not successful upon initial theatrical release, but, thanks to a strong buzz and the release of VHS tapes these films circled back to prominence after a failure to launch. Grant writes, “Movies that represent the fast food of cult rather than the slowly simmered fare like Blade Runner, which became cult when released on video (VHS) after its theatrical run.”[23] Blade Runner (1982), suffered when released two weeks after the mainstream success of the Science Fiction film E.T. (1982). Due to the fact that they were both of the same genre, and E.T. is a family friendly science fiction film, Blade Runner found itself with low box office numbers upon release.[24] With the rising popularity of the VHS format, however, Blade Runner managed to circle back around as many Science Fiction fans grew to be fond of this film.

Midnight movie showcases have existed within the film community for decades. Different films of different genres are booked for midnight showcases yet there seems to be a common trait amongst these films. In David Church’s article, “Freakery, Cult Films, and the Problem of Ambivalence” David writes that “Its development was also linked to the proliferation of a camp aesthetic that ironically privileges excessive forms of bad taste associated with cultural debris.”[25] The key word within this quote is the ‘excess’. Midnight movies typically revel in playing up violence, sexuality, and all other cringe worthy material. Eraserhead (1977) had a strong run within the midnight movie circuit. This bizarre and surreal horror film confuses and shocks most mainstream audiences but select cultist’s love this film. In the article “Midnight S/Excess”, Gaylyn Studlar writes: “For example, the entire pattern of visual iconography in David Lynch’s Eraserhead suggest the “filthy foods” of a menacing femininity, simultaneously a lack and fluid (vaginal) too-much-ness.”[26] While this excess may turn away a more mainstream prone audience, midnight move consumers love this film.

Donnie Darko (2001) did poorly in its initial theatrical run and was deemed a failure by many. Donnie Darko managed to net a strong fan base that created a buzz around the film outside of the realm of box office numbers and critical reviews. With this word of mouth, Donnie Darko began playing in New York as a midnight movie. This film played at the Gene Siskel Theater in New York to packed houses weekly.[27]

Tim Corrigan writes, “No film is naturally a cult film; all cult films are adopted children.”[28] This quote shifts the focus away from cult films and on to the cult fans. This is essential because there truly is no definitive definition of a cult film, instead, the true meaning of a cult film lies within the audience that surrounds the cult film. A second quote of importance belongs to James Card, who in his article “Confessions of a Casablanca Cultist” writes: “One sign of a cultist is that he/she treasures the film’s dialogue.” This is important as it will continue to be relevant when focusing upon cult fans.

Anyone that loves the film Pulp Fiction (1994) is well aware of what a “Royale with Cheese” is. There are some people who take pleasure in re-watching Pulp Fiction and quoting multiple lines throughout the film. Now, one could imagine the amount of pleasure derived from watching Pulp Fiction and quoting multiple lines throughout the film while in a theater filled with other fans who adore this film. This is what it means to be a cultist, and for a film to be a cult film. Not in the sense strictly that one must love every word of the movie, but instead that one can find self-identify while viewing this film with others who have the same passionate feelings.

This is exactly how the film Rocky Horror Picture Show (1979)[29] came to be the massive cult success that it is today. The sing along nature of the film, combined with patrons who dress as characters from the film and act out sequences, makes this film an experience that transcends the film screen. Upon purchase of a midnight showcase ticket to Rocky Horror, one does not look forward to simply watching a movie, but instead they look forward to a functioning role in an experience. Robert E. Wood writes “As one of the film’s (Rocky Horror) lyrics suggests, ‘there’s a light in the darkness.’ That line usually provokes a display of cigarette-lighter flames from the audience, act fraught with ceremonial significance in its own right.”[30] This behavior occurs at every midnight showcase of Rocky Horror and is performed like a ritual, quite similarly to how fans will dress as members of the cast and perform for the audience.

This ritualistic activity does not take place only within the confines of the movie theater, it can happen outside of it as well. Cinephiles tend to enjoy the film The Big Lebowski (1998), yet, there is a certain sect within the film community that has elevated this film to cult status. So much so, that there is now a “Lebowski Fest”[31] in which fans of the film gather dressed as “The Dude” or any of the other characters from the film and interact with one another. This is no different from a comic convention in which comic book fans arrive at a certain venue dressed as their favorite comic book characters and converse with fellow fans. Great importance exists, however, in how it is the fan base that allows these films to have the cult like status. If cultists did not feel this type of way about The Big Lebowksi, The Lebowski Fest would not have been created.

This can be applied to the famous television show Dr. Who. I have attended to a number of midnight showcases for various films I love, but none possess the cult like behavior displayed by fans of the show Dr. Who. At a NCM special screening for Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013), a special episode in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the television show, fans arrived dressed as Dr. Who and some even possessed the special Dr. Who gadget, the sonic screwdriver. This scenario raises an interesting point in which one must discern where the line is drawn between mainstream fandom and cultist behavior. It also introduces a cult mode of spectatorship.

In the digital and technological age, there is no line between mainstream fandom and cultist behavior. Matt Hills writes: “Films can become cultified by the ‘unfolding consumption’ of online fans”.[32] There is no question that the Star Wars franchise exists as a mainstream product for mainstream consumerism, but that does not mean that there are not cultists that surround that franchise. I am not a cultist of the Star Wars franchise but I am however aware of the cultist fan base that surrounds the film franchise. This cult fan base exists within online forums, fan made content and even fan theories. Some cultists are so dedicated to this franchise they have taken time to try and interpret the text of Star Wars films in new and unique ways.

This mainstream line is imperative to discuss as it displays the true nature of cult films and the cultists that surround them. There is no true boundary as to what can be considered a cult film and what cannot. Star Wars fans that explore various fan theories on Reddit are no different than Rocky Horror fans who dress up as Dr. Frank N. Furter and attend midnight screenings to belt out lyrics as they play across the screen. As a matter of fact, cultist fans of Star Wars are just as likely to wear Star Wars inspired gear or even dress up in costumes as their favorite characters to attend screenings of the film.

No film is created as a cult film; no director or screenwriter begins pre-production in an attempt to make a cult film. Instead, it is up to the fans to decide what films will ascend to the cult status that is so cherished within the film community. Cultist fan bases display the true power of media users. Those who use media can interpret however they want and they can also bend how films are viewed in the grand scheme of media reception by elevating movies to the cult status and giving them an audience outside of mainstream consumerism and box office success. The definition of a cult film is so elusive because any film can become a cult film.

Notes

[1] Tim Dirks, “Cult Films,” AMC/www.filmsite.org, December 12, 2016. http://www.filmsite.org/cultfilms.html

[2] Gregory A. Waller, “Midnight Movies: 1980-1985: A Market Study,” in The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason 1991, ed. J.P. Tollete (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1991), 172.

[3] David Church, I.Q. Hunter, “Cult Film: A Critical Symposium” Cineaste, Winter 2008/November 10th, 2016. https://www.cineaste.com/winter2008/cult-film-a-critical-symposium/

[4] David Church, “Cult Film: A Critical Symposium” Cineaste, Winter 2008/November 10th, 2016. https://www.cineaste.com/winter2008/cult-film-a-critical-symposium/

[5] Alan Travis, “Retake on Kubrick film ban,” The Guardian, September 10th, 1999/December 1st, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/1999/sep/11/alantravis

[6] Walter Hill, The Warriors, DVD, directed/performed by Walter Hill & Michael Beck & James Remar (1979; New York City: Paramount Pictures.), DVD.

[7] Danny Peary, Cult Movies: The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird, and the Wonderful (New York: Dell, 1981) 379.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Dennis Hopper, Easy Rider, DVD, directed/performed by Dennis Hopper & Peter Fonda (1969; Los Angeles: Raybert Productions/Columbia Pictures,) DVD.

[10] “Box Office/Business for Easy Rider,” IMDB, December 1st 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0064276/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus.

[11] Mark Shiel, “Why Call them ‘Cult Movies’? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960’s,” Scope Online Journal of Film Studies (2003) : 12, accessed November 10th, 2016, http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/scope/documents/2003/may-2003/shiel.pdf

[12] Kevin Smith, Clerks, directed/performed by Kevin Smith (1994; New York City: Miramax Films,) DVD.

[13] “Box Office/Business for Clerks,” IMDB, December 1st 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109445/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus

[14] Korey Coleman, Space Jam, directed by Korey Coleman, performed by Michael Jordan and Bill Murray (1996; United States: Warner Brothers Family Entertainment,) DVD.

[15] Randal Kleiser, Grease, directed by Randal Kleiser, performed by John Travolta (1978; Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures,) DVD.

[16] Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton, Cult Cinema: An Introduction (Chichester West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.) 176.

[17] John Hughes, The Breakfast Club, directed by John Hughes, performed by Emilio Estevez and Molly Ringwald (1985; United States: Universal Pictures,) DVD.

[18] Danny Peary, Cult Movies: The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird, and the Wonderful (New York: Dell, 1981) xiii.

[19] Roger Chapman and James Ciment, Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices. Armonk, (NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2010), 163.

[20] Ian Haigh, “What Makes A Cult Film?”, http://news.bbc.co.uk/, May 3rd 2010/November 10th 2016, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/8640334.stm.

[21] Clark Collis, “The Crazy Cult of ‘The Room’,” Entertainment Weekly, December 12th, 2008/December 1st, 2016, http://www.ew.com/article/2008/12/12/crazy-cult-room.

[22] Barry K. Grant, “Science Fiction Double Feature: Ideology in the Cult Film,” in The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason 1991, ed. J.P. Tollete (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1991), 124.

[23] Ibid, 123.

[24] “Box Office/Business for Bladerunner,” IMDB, December 2nd 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0083658/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus.

[25] David Church, “Freakery, Cult Films, and the Problem of Ambivalence,” Journal of Film & Video 63, No. 1 (2011): 8.

[26] Gaylyn Studlar, “Midnight S/Excess: Cult Configurations of ‘Femininity’ and the perverse,” in The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason 1991, ed. J.P. Tollete (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1991), 140.

[27] Scott Tobias, “The New Cult Cannon: Donnie Darko,” AV Club, February 21st, 2008/December 2nd, 2016, http://www.avclub.com/article/the-new-cult-canon-idonnie-darkoi-2179

[28] Timothy Corrigan, “Film and the Culture of Cult,” in The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason 1991, ed. J.P. Tollete (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1991), 26.

[29] Jim Sharman, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, directed by Jim Sharman, performed by Tim Curry (1975; United States: Twentieth Century Fox), DVD.

[30] Robert E. Wood, “Don’t Dream It: Performance and The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” in The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason 1991, ed. J.P. Tollete (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1991), 158.

[31] “Lebowski Fest,” accessed December 12, 2016, https://lebowskifest.com/.

[32] David Church, Matt Hill, “Cult Film: A Critical Symposium” Cineaste, Winter 2008/November 10th, 2016. https://www.cineaste.com/winter2008/cult-film-a-critical-symposium/