Category: Issue 4

-

Queer Christina: The Representation of LGBT Characters in Pre-Code Era Films

Historically, the representation of queer characters in film and onscreen is very poor. They are often one-dimensional stereotypes portrayed through gender inversions — the gay “pansy” or the “butch” lesbian. Despite the presence of LGBT persons in front of and behind the camera, showing homosexual characters in the early years of Hollywood “in anything but…

-

Real Monsters and Real Disgust: Comparing Reception of FREAKS and FRANKENSTEIN

INTRODUCTION Scholarship surrounding Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) mostly includes discussion about public perception of disability. This discussion is certainly warranted, but I am hesitant to place sole responsibility for the film’s poor reception on said perception. Indeed, to place such emphasis on viewer attitudes about disability is to ignore systematic exploitation and “othering” of disabled…

-

The “Utterly Impossible” Story of BLONDE VENUS

“As soon as you stopped singing and started luring men into the bedroom, that’s when the moral outrage would kick in.”[1] This quote sums it up best when referring to the 1932 pre-Code film, Blonde Venus.[2] Starring Marlene Dietrich, and directed by one of Dietrich’s biggest collaborators, Josef von Sternberg,[3] Blonde Venus was set to…

-

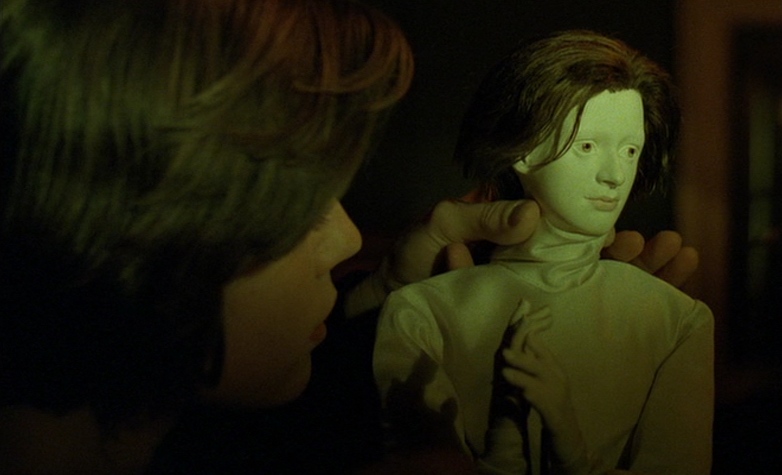

Scene Analysis: Subversion of Gender Roles in THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VERONIQUE

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Double Life of Veronique is remarkably unique in the way that it flips the power balance between men and women. This is most notable in the marionette scene. About half an hour into the film Veronique and her students watch a puppet show about a ballerina who breaks her leg the first…

-

The Rise of Movie Palaces During the Silent Era

Following the rise of the film industry in the early twentieth century, the Movie Palace became the primary manner in which motion pictures were showcased. Several factors, most notably America’s booming economy and heavy investments in the film industry, led to the rise of the Movie Palace. These were more than just buildings that presented…

-

Is Detroit a Cinema Desert?

Detroit is an underserved city for film exhibition, specifically first-run theaters. This lack of theaters in Detroit is largely due to suburban fears multiplied by poor media representation. As a historically segregated city, the overall absence of theaters serves to further stratify Detroit across racial lines and disenfranchise black Detroit residents. Not only is film…

-

Love, Money, and An Unnamed Procedure: Frank Borzage’s BAD GIRL

There is a sweetly comic tension running through Frank Borzage’s romantic comedy-melodrama Bad Girl (1931) that arises from trying to discern how we are to regard the lower-class New York City couple at its center. Adapted from a 1928 novel by Vina Delmar, and a 1930 play by Delmar and Brian Marlowe, Bad Girl follows…

-

Hitchcock: Depicting Homosexuality in ROPE

Shot Shot Description 00:00 Screenshot 1a CU Opening image. Philip strangles David with a rope while Brandon holds David. 2:49 1b MS Brandon checks for David’s heartbeat to make sure he’s dead. Shocked Philip watches.…

-

Bette Davis: Commodifying the Feminine

Hollywood has always been a business, and for most studios in the early 20th century their main profit drivers were the men and women who brought films to life on screen: the actor. In the days of early silent films, actors were largely anonymous thanks to the scattered system of film distribution that was in…

-

The Star Image of Gene Kelly

Whenever the topic of film musicals is discussed, many famous stars are remembered. The late 1940s to the 1950s was a period that involved a number of unique and talented performers, whether they were actors, singers, dancers, or possibly all of the above. Gene Kelly, a master of all three, was one of the most…